I would never have been comfortable calling myself a feminist, but, indeed, for most of my life, I would never have been comfortable calling myself feminine. I didn’t particularly identify with, as the kids say these days, anything in particular about womanhood. In college, a friend was recounting being very attracted to a woman he saw in a bookstore: he commented that she had this way of looking at him indicating that she knew he was looking at her like that, the way that men look at attractive women, and he called it “very feminine” and I asked him what that word means to him, “feminine.” It was very late at night, and we had been drinking gin and tonics, and he was frustrated by the question: isn’t it obvious what it means? But, no, I did not think that it was.

In part, this was from having denied that there was really such a thing as femininity for too long. Certain undeniable facts about one’s body notwithstanding, weren’t men and women mostly the same? Didn’t we share a common culture and a common evolution, many of the same emotions, needs, desires? Surely we were more alike than different. I liked and was good at math; among my favorite pursuits were playing with a chemistry set, being outdoors, and reading novels about pirates and seafaring. I thought the best thing you could be was tough.

I identified strongly with Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn as they chafed under the constraints of civilization, even as my Good Southern aunt gave me lessons in, for example, getting into and out of cars in the most delicate and ladylike fashion, so as not to expose myself, unwittingly, to men who did not love me. “This is a fake problem, a problem caused because you won’t let me wear pants to church!” I screamed, but only internally, because this aunt brooked no backtalk.

And so, because I identified with boys, I thought that we were basically the same, except they were allowed to just wear pants to church and therefore had the freedom to get in and out of the car in any kind of unruly fashion they chose; they could tumble and jostle around without exposing their “private parts,” which seemed an injustice to me, one I could perhaps escape by building a raft and lighting out for the territory. These were constraints imposed by a wrongheaded society — governed by the pious and grumpy old ladies who were no fun at all — not an inherent difference between the sexes, in my mind.

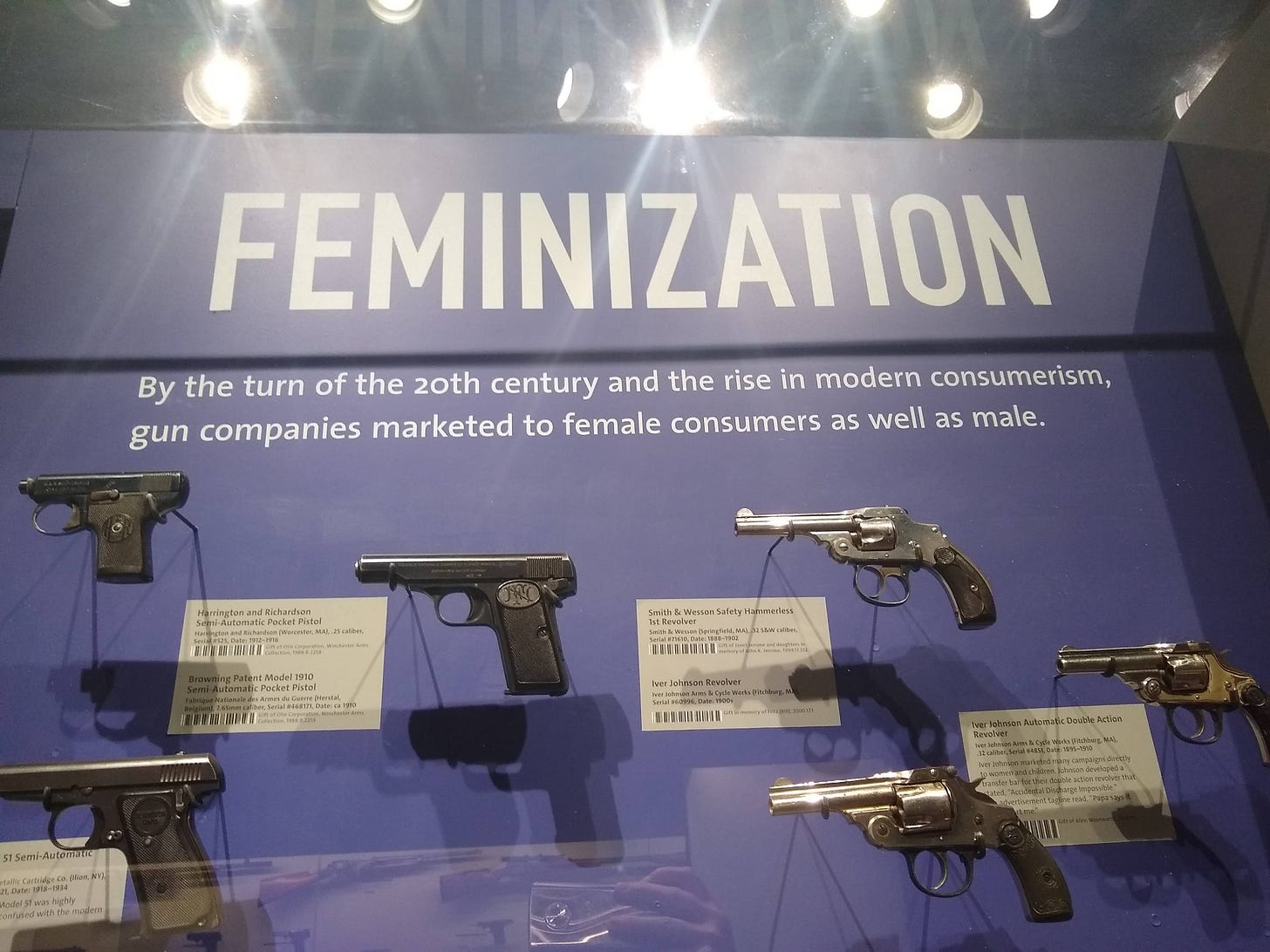

While I was reading all these books about and learning to identify with male characters, pursuits, and norms, were little boys reading books with girl protagonists and equally identifying with the inherent equality of and dignity of all humans, regardless of sex? Ha, you must be joking. From what I hear, some teachers have made reading lists in the public schools that try to correct this historic imbalance somewhat and are now the reason boys are not doing as well as girls at school; the feminization of school by female school teachers is harming boys, so I hear.1 I hear the complaints that sound to my ear much the same as my own internal complaints about the pious southern aunts who were always trying to make us behave in church: we are all suffering under the tyranny of the female. Interestingly, men have had this complaint for a very long time, perhaps forever: the eternal discontent.

So, while I had thought we were the same, boys and girls were certainly not treated the same, and boys did not grow up with the same opinion of our essential sameness. And those are real differences between us. That is a reality we come up against, as we struggle to get out of a car while keeping a dime firmly held between our knees. These are the realities that we must face when we try to understand each other.

Recently, we went on a very long road trip. I love road trips; they always bring me back to that Huck Finn spirit. I love being in a new place and seeing new things each day; I love forcing myself temporarily out of some comfortable habits. I love standing on the overlook at the Black Canyon of the Gunnison and whispering under my breath, “What a country,” only to have the stranger standing next to me, experiencing the same awe as me, whisper back, “Amen.”

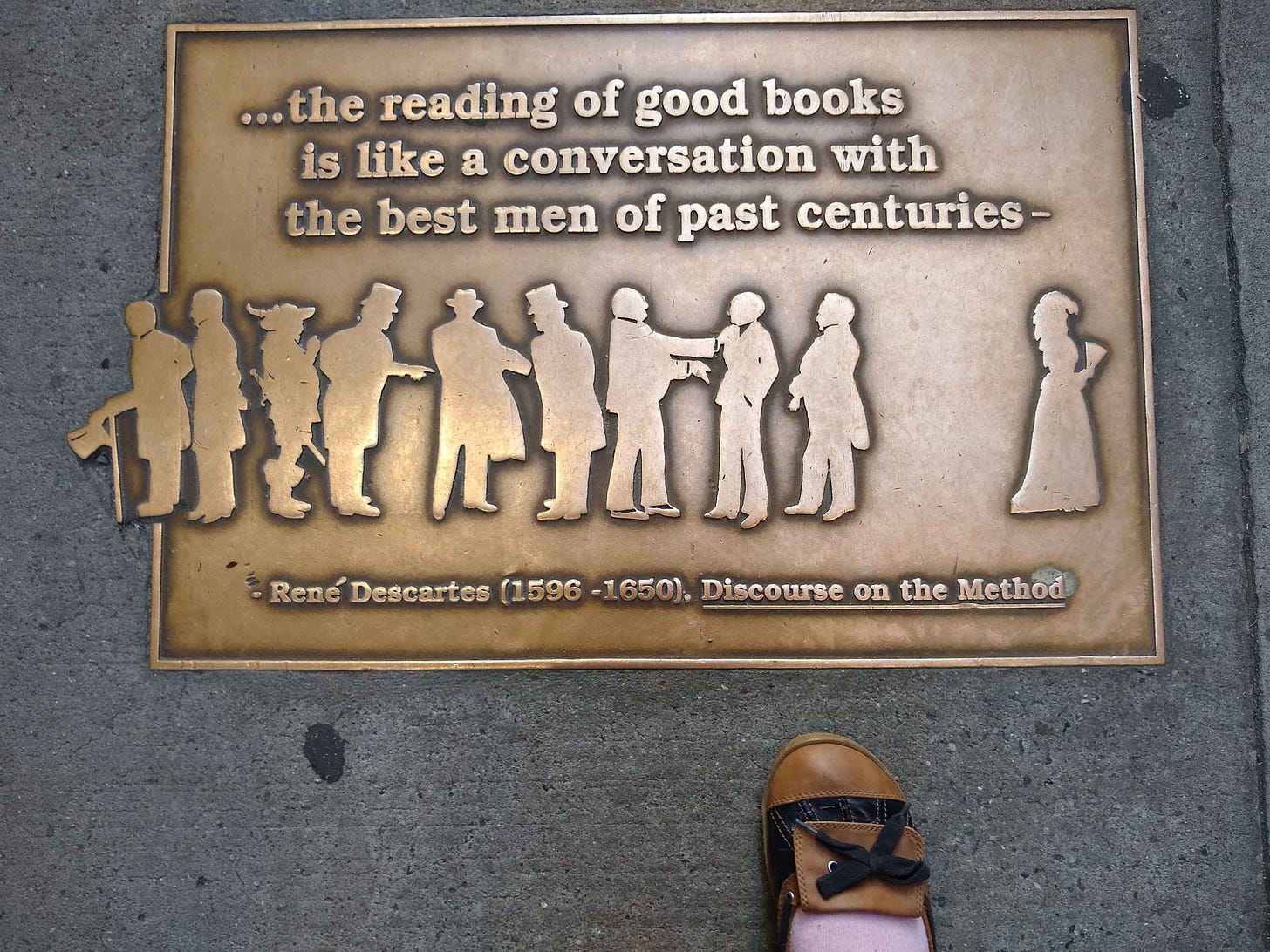

I bought a book by Matthew Crawford (who wrote Shop Class as Soulcraft, a book I have admired) to take along on this trip. It’s called Why We Drive: Toward a Philosophy of the Open Road. I thought it would be a perfect thing to take along on a road trip and read. When I first receive a book I am very excited to read, I often flip through it and skim a few pages here and there to get a sense of it, and read the table of contents in anticipation. In this particular book, I happened on a section ostensibly praising “redneck women.” I was immediately interested, and I stood there and read the whole section. And what I think now is that we should, as a culture — I’m not suggesting any kind of legal censorship, you understand, but just a cultural accord — impose a kind of moratorium on men writing books or having access to microphones. They’ve said enough, they’ve written enough, their opinions are well known and have become, frankly, very tired.

Consider:

The lower middle class is where patriarchy is said to remain the most unreconstructed. Yet such patriarchy, if that is what it is, appears to be quite compatible with cocksure women who seem to have no problem controlling their men — if necessary, by berating them to “man up.”

This is the dumbest take on this I have read in my entire life. Or, no, it isn’t, exactly — it’s that this man is supposed to be a serious thinker, an author of three books who works at the University of Virginia’s Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture, and this particular take is at the same level of thinking I expect from Twitter reply guys. He goes on to cite examples of what he means: first, a woman who worked in the restaurant industry and figured out she just needed to reply in kind to the men in the kitchen subjecting her to continual sexual harassment (gee, no other woman has ever thought of trying that before, thanks!); and, then, Katey Sagal’s character in Sons of Anarchy. “[She] rules not as a mitigating or elevating feminine influence, but from within the male norms of the gang itself, which she entirely shares.” It seems that if you want to be a woman that Crawford can respect, you have to fully adopt “male norms,” talk the way men do, ride a motorcycle, whatever. Ladies, have you tried these things?2

It’s not offensive, heaven forbid, it’s merely dull. I have done all of this, long before Crawford ever even conceived this book; I have subverted my actual feminine personality in all the male-dominated spaces I have been in and, you know what, I hate it. I hate pretending to be someone I am not, and I’ve reached an age and a comfort level with who I am that I am not going to do it anymore. It should not take more than a single second for a guy like Crawford, who routinely sounds like Huck Finn bemoaning the tyranny of the church ladies who want to make him behave in ways that are not true to who he is, to figure out why this might be.

So, as I say, we need a moratorium on men talking in public until we can figure out what the hell is going on. If they can get a Ph.D. in philosophy and still not see what “unreconstructed patriarchy” might have to do with women adopting and fully sharing “male norms” and berating men for not living up to them, then I really do not think they should be writing books. Let them clean up after dinner while the ladies have time to talk and think.

As a family, we’ve been reading (for me it’s a re-read, but for Chris and the boys it’s a first read) Shop Class as Soulcraft, which I have mentioned in a previous post.

It’s been more frustrating in this regard than I remembered it being. I do still think it makes good points and a good argument, overall, and it doesn’t bother me that it relies so heavily on the example of repairing motorcycles to illustrate the points he is trying to make. Interestingly, that aspect of it bothers Chris more than it bothers me, and I understand his complaint. As he says, a machine — whether the motorcycle or a computer, if you are a computer programmer instead of a motorcycle mechanic — can give you feedback about whether you are doing something correctly, but it cannot give you feedback about whether what you are doing is important or good.

The chapter of Shop Class as Soulcraft we just finished last night was particularly frustrating. A major theme of the book is that it is good to force yourself to contend with material reality, particularly with the ways in which it will not yield to your will. In material reality, some things can be affirmatively known: the motorcycle either runs or it does not, the oil either leaks or it does not. And the ways that you can put together a motorcycle engine and have the machine still work are not subject to your infinite will and creativity.

The point of this chapter is that another way in which we must confront hard, unyielding reality is in our dealing with others and their priorities. “To respond to the world justly,” he writes, “you have to see it clearly, and for this you have to get outside your own head.” Our own will and proclivities must be disciplined by a “circumspect regard for others,” he says. The extended anecdote he focuses on to illustrate this point involves a motorcycle that Crawford doesn’t really consider worth fixing but the customer seems willing to pay for; the engine turns out to be tricky and require more of Crawford’s time to repair than he anticipated, so he lies on the service bill and knocks a considerable sum off the labor charge. He is not comfortable charging this customer for the full amount of time because some of the time he spent was merely following his own curiosities, and that’s worth something to Crawford but surely not to the customer. So, here his will confronts a different kind of hard reality, and as when he is faced with a motorcycle engine, he (partially, at least) fits himself to the situation rather than asserting his own unlimited self.

It’s not ideal as an example of moral responsibility, perhaps, but this man is very wrapped up in motorcycles and hard pressed to come up with any examples outside of that. Nevertheless, it is true that in any interaction, one of the limitations on your own will and activity has to be a regard for others, a consciousness that others have needs and desires separate from yours and yours are not the only things that determine reality. He cites Amy Gilbert: “practical wisdom entails ‘the full appreciation of the salient moral features of the particular situations we confront’” and concludes, “The presence of others in a shared world makes [being a clear-sighted person who looks around and sees the whole situation] both possible and necessary.”

I agree entirely with all this, but — there is a big but coming here! — earlier in the chapter he briefly recounts a scene in which he was at an academic conference regarding the death of beauty and the disenchantment of the world. He writes:

“Speaking up for my own sense of enchantment, I pointed out, from the audience, the existence of beautiful human bodies. Youthful ones, in particular. This must have touched a nerve, as it was greeted with incredulous howls of outrage from some of the more senior harpies.” (emphasis added)

This is incredible. It would be understandable if this was a young man’s spontaneous thought in the moment of being howled at: “these harpies, they are just jealous!” But he is writing a book, for heaven’s sake, and writing it many years later. He has had ample time for reflection, to understand what the “salient moral features” of that situation and of calling older women “senior harpies” might be.3 He does not record here his exact words or what precisely was under discussion at the time he said them; he does not record precisely what these “senior harpies” said — or, excuse me, howled. In a book in which the entire argument hinges on becoming more aware of your own physical, cognitive, and viewpoint limitations, he is so painfully unaware of his. He makes the case for dealing justly with the world by getting outside your own head, but the realities he is willing to bump uncomfortably against seem limited to those that can be built out of metal.

Men like Crawford want women to speak like men, think like men, act more like men, bend themselves to “male norms” so that men can go comfortably about their business. He lauds women who are tough, but tough can only mean willing and able to adopt male norms — not to fight against them or even voice disapproval of them. He wants us to pretend that reality is not what it is, that we have not been treated differently according to the ways our bodies appear in the world, for our entire lives. He does not want to peek under the hood of this particular engine and face this particular unyielding reality. This is contrary to his entire point, but he never sees it. To be fair, many women also never see it, because, of course, we have been thoroughly brought up to accept those standards and norms as the standards and norms of our shared society. They may be unfair, but that’s life.

It is a given that men’s voices and experiences, men’s ways of talking, are the default and have universal appeal. This is why women can read any books, including ones in which Philip Roth goes on about his prostate for 30 pages or more and come out of it talking about how it’s really about the humiliations of aging, a human universal, but men struggle to understand or sympathize with ones written by women. Men say they don’t need external validation (so why should women need it?) not realizing that validation is like money: it is very easy to say you don’t need it when you have enough of it.4 While bombarding us from all sides with their thoughts and feelings, they complain that no one cares about men’s feelings. Has no one considered poor Matthew Crawford and how much it means to him that women be tough and sexy?

My favorite part of Naomi Alderman’s book The Power5 is not so much the story itself but the epistolary framing. In the series of letters between the ostensible author of the book, “Neil,” and his friend, “Naomi,” they are arguing about whether men and women have “always” been the way they currently are, with men the more weak and peaceful sex and women the stronger and more violent sex. Naomi claims it makes sense that women would have always been stronger and more violent because they have babies to protect. Neil claims that it’s irrational to suppose there was a time or place where female babies were commonly aborted, as that doesn’t make any evolutionary sense. The worst excesses perpetrated against men in the world of The Power could never have been perpetrated against women, he thinks; it just wouldn’t make sense to do that. But, ultimately, he says it doesn’t have to matter whether this or that happened before the world of The Power:

The world is the way it is now because of five thousand years of ingrained structures of power based on darker times when things were much more violent and the only important thing was — could you and your kin jolt harder? But we don’t have to act that way now. We can think and imagine ourselves differently once we understand what we’ve based our ideas on.

Maybe the ways we historically have been do not have to determine who we are now. Maybe women are the ways they are for good reasons that people like Crawford simply haven’t bothered to understand. Maybe tough isn’t always the best thing you can be; maybe the best thing you can be is responsive to the situation you find yourself in, whether it requires toughness or softness, which is more difficult than it sounds, and nettlesome because it means you have to get outside yourself to do it. Maybe it’s salient that Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn are literally children, with a child’s understanding of the world.

Anyway, when I write my own (next) book, it will not be about motorcycles but about the things many people say constitute the most important job in the world, which will, somehow, render it a book for women instead of a serious book.

I don’t want to sound too awful glib about this; perhaps some of the criticisms are correct. But it seems to me that the finding that having female teachers is bad for boys but having male teachers is not bad for girls is just a finding that we are still a very misogynistic society: both boys and girls respect male teachers and learn from them, but boys are unable to do so for female teachers. All I can say is I have read mostly books written by and for boys and men, with male protagonists and weak female characters who are more like plot devices than characters, and, y’know, what’s good for the goose is surely good for the gander.

This reminds me of a blog post I once read by a famous (famous in the world of functional programming, anyway) professor of computer science who posted on his door an essay about how women can’t handle being software programmers, even though he admitted the arguments were rubbish, to test the women students, to see how they would handle it. The fact that some women students went over his head and complained to the dean or whatever is why he simply can’t respect women. They should instead have wasted a bunch of time writing logical arguments against something that, by his own admission, was rubbish and therefore did not warrant that amount of activity on their parts. The fact that he is testing women students to see if they are worthy of his respect, and not male students, is proof enough, in my opinion, that he’s a pretty irremediable sexist and should not be allowed to interact with students, but he is famous so there’s that.

You can get equally howled at by male harpies, whatever they might be called, by suggesting that contexts matter and that, for example, an academic lecture is not the ideal place for inserting pictures of naked women in order to make crude jokes that are only tangential to your point.

And, men, I’m sorry but things like paychecks and promotions are external validation.

If you haven’t read it, it’s about a series of events in which the women of the 21st century suddenly develop an ability to deliver a strong electric jolt from their hands, which sets off a chain of cataclysmic events. Five thousand years later, a man named Neil has written a book about these events and how women became the dominant sex, and the book is framed by letters between him and “Naomi” in which she’s arguing that it seems unlikely that women weren’t always the dominant sex, because we have no historical records of a time when women weren’t the dominant sex.